Backpacks, Outdoor Gear and EDC | The Best Products to Buy from August 2024

From sleek EDC knives to lightweight travel packs, August dished up a quality selection of new releases for daily use and adventures further afield. Discover the month’s best new gear below…

EDC

GiantMouse Knives x Castle & Key Distillery Collaboration

The GiantMouse Knives x Castle & Key Distillery Collaboration salutes premium craftsmanship and a respect for tradition, featuring a limited-edition knife paired with a Castle & Key cask-strength Single Barrel Bourbon. The Castle & Key Distiller’s Blade is designed by Jens Ansø and Jesper Voxnaes and produced in Maniago, Italy. It comes in two editions, both incorporating copper, vital to bourbon production, and a design element referencing the skeleton keyhole-shaped water source on the distillery property.

The “Blackout” edition features black titanium handle scales, a dark PVD-finished CPM-20CV stainless steel blade, and copper accents. Each of these 100 numbered knives is paired with a corresponding numbered bottle of cask-strength Castle & Key Single Barrel Bourbon. This boxed set is available at the Castle & Key distillery shop. There are also 100 units of the Castle & Key Distiller’s Blade in a “Blue Edition”, featuring blue anodized titanium handles and a CPM-20CV stainless steel blade. These are sold individually, with fifty units released on CastleAndKey.com and fifty released on GiantMouse.com.

Septum Studio HUNT XR Flashlight and Pry Bar

Want to get more out of your gear while carrying less? Septum Studio offers a multifunctional EDC tool in the Hunt XR, a mini flashlight and pry bar in one. The Hunt XR offers multiple light modes, five LED colors, and SOS and beacon light options. The pry bar also serves as a screwdriver and scraper, while an included clip makes it easy to attach to a bag or cap. Crafted with lightweight but durable titanium, the Hunt XR is currently available to preorder through Kickstarter.

GiantMouse ACE Bleecker

GiantMouse has recently launched the ACE Bleecker, which continues their line of versatile EDC blades inspired by landmarks. Named after Bleecker Street in Manhattan and designed to embody the bohemian spirit of Greenwich Village, the Bleecker is a sleek, modern “gentleman’s” folder created for practical and discreet everyday carry. The knife boasts a 3.35″ Magncut blade with a thickness of 0.118 inches and has a weight ranging between 85g and 102g, depending on the handle choice (available in Carbon Fiber and Titanium).

Jetbeam E26 Wedge-Style Flashlight

Wedge-style flashlights have become very popular with the EDC community for several reasons. Due to their flat shape, they are comfortable to hold, more compact, and often offer multiple lighting options, making them very versatile.

The Jetbeam E26 is their take on this popular trend, and it was launched through a successful Kickstarter campaign. It features a bright white LED, UV light, and a laser pointer. This flashlight can provide up to 1000 lumens of brightness with multiple light modes and is designed to withstand harsh conditions with water resistance and a robust construction. It measures 4.25 inches long, is less than an inch wide (0.91 inches), and weighs just 67 grams without the battery. It runs on a single 1700mAh battery, providing up to 65 hours of usage. The Jetbeam E26 flashlight is available in four different color options.

Urban

Reigning Champ Heavyweight Jersey T-Shirt

The foggy skies and crisp weather have arrived, and so has Reigning Champ’s Heavyweight Jersey Collection. The collection features a range of boxy fit essentials made from their heaviest jersey fabric yet. The collection includes the Shootaround 7” Shorts and a T-shirt available in three colors. The T-shirt features drop shoulder construction, a 1×1 rib collar, semi-raglan sleeves, and signature flatlock construction. These items are designed to be worn loosely and drape beautifully. Be sure to check the sizing for your preferred fit.

Mack Weldon The ACE Straight Leg Sweatpant

Mack Weldon has taken their bestselling sweatpants and is now offering them in a classic silhouette. The ACE Straight Leg Sweatpant is made with ultra-soft French terry for a premium feel that will never fade. It includes a woven poplin waistband with a drawcord and a reinforced kickplate hem to maintain its shape wear after wear and wash after wash.

Fall 2024 Collection from Bandit Running

As one of the newest entrants into the space, Brooklyn-based Bandit Running has come out of the gates, well, “running”. Their Fall 2024 Collection just dropped this week, and it’s their most impressive offering to date. It features a whopping 92 pieces, including 11 new silhouettes and updated favorites. You can find singlets, compression tops and crops, performance tees, tanks, shorts, tights, outerwear, hoodies, socks, and hats. The theme is “Staying the Course” and is inspired by self-reflection and growth in running. It uses Cubist art influences, and you’ll find a palette of cool grays, stoney blues, warm browns, and rich reds. The collection is available online, at Bandit retail stores in Brooklyn and NYC, and select global partners.

Outdoors

Filson FW24 Men’s Collection

With cooler weather on the horizon, Filson’s FW24 men’s collection offers functional, durable wardrobe staples that will keep you warm while standing up to daily wear in urban and outdoor environments alike. The collection offers new colorways across classic pieces such as the Lightweight Alaskan Guide Shirt, Vintage Flannel Work Shirt, and Jac-Shirt. Additionally, outerwear pieces such as the Beartooth Cruiser Vest, Tin Cloth Field Jacket, and Prospector Hoodie are versatile grab-and-go options when the cooler weather starts to bite.

Skida Flow State Collection

Skida is a well-known brand that offers a variety of sun and snow protection products with many design options. They have partnered with Los Angeles-based mixed media artist K’era Morgan, also known as Flow State, to feature around a dozen new designs for their FW24/25 collection. The patterns in the collection feature weaving lines and dots, intended to express complex emotions while entering into a “flow state,” a focused state of being. The Flow State collection includes a wide range of Skida’s products, such as Sun and Snow Tour, Running Hats, Headbands, and more.

VERO Smokey Bear 80th Birthday Watch

Did you know Smokey Bear’s fire prevention efforts are the longest-running public service announcement in United States history? Vero Watches is celebrating the 80th Anniversary of Smokey Bear’s inception with two new colorways based on the now-sold-out release from last year.

Offered in Forest Green and Brilliant Blue dials, the watches are adorned with Smokey at 12 o’clock and come in a 38mm wide bronze case. Over time, the bronze case will develop its own natural and personalized patina, giving each watch a unique look. The Anniversary Edition watches are powered by an automatic Seiko NH38A movement with 41 hours of power reserve. Finally, they are paired with a leather strap with bronze hardware but also come with a black canvas NATO strap to swap out. 10% of profits go towards supporting the US Forest Service.

NESTOUT Rugged Outdoor Power Banks, Solar Panels, & LED Lamps

Established in 2018 by the Japanese brand Elecom and introduced to the US market in 2023, NESTOUT provides modular power banks, light accessories, and solar panels that are shockproof, dustproof, and waterproof. The company has won multiple awards, including the IF Design Gold Award and Good Design Award. In the competitive market of power banks, NESTOUT stands out with its unique offerings. Their power banks are available in three capacities: 5000 mAh, 10,000 mAh, and 15,000 mAh, and are designed in three muted, desert or military-inspired colorways. The silhouette of the power banks is reminiscent of army canteens, giving them a unique look. The ports are located at the top of the banks and are covered with threaded caps to protect against dust and water. NESTOUT’s modular design allows seamless integration with custom-fit accessories, such as two LED lighting options: the LAMP-1 Gear and FLASH-1 Gear, which attach to the USB-A output of the power banks. The light accessories also come with a mini tripod for placement under the power banks and a storage pouch for all three items when not in use. In addition to recharging with an AC adapter, NESTOUT offers 2-panel and 4-panel solar chargers capable of generating up to 28W for charging devices. Overall, NESTOUT is setting itself apart with unique features and innovations.

EXPED Mega Pump

If you’re tired of wasting time inflating and deflating your sleeping mats or other inflatables, EXPED has the perfect solution. Their newly introduced Mega Pump can quickly finish the job in just over a minute. It has a rechargeable 2500 mAh battery with a USB-C port, providing up to 25 minutes of run time. Although it is designed for use with EXPED sleeping mats, it comes with adapters that allow the Mega Pump to be used with certain non-EXPED sleeping pads and inflatables. And weighing just 12.3 oz, it has a portable design, making it perfect for camping and outdoor activities.

Arc’teryx Solano Jacket

The Solano is a versatile jacket that leverages GORE-TEX INFINIUM fabric for windproof, breathable, and rain-repellent protection. It’s ideal for cold-weather hikes and combines protection with a refined design featuring articulated patterning for ease of movement. It also has a hybrid construction — smooth in the sleeves and knit in the body for breathability and comfort. It is currently offered in five colors across a full-size run. The Solano is a Regular fit item in Arc’teryx’s line.

Travel

RAWROW x STAPLE Capsule Collection

New York streetwear apparel brand STAPLE and South Korean carry brand RAWROW have teamed up on a limited-edition capsule collection that blends STAPLE’s signature color palette and design perspective with RAWROW’s modern travel silhouettes. The capsule collection includes the RAWROW x STAPLE R Trunk Frame in both 84L and 88L options, the RAWROW x STAPLE String Backpack, and the RAWROW x STAPLE String Sling Bag.

Bellroy Lite Travel Pack

When you’re traveling with a carry-on backpack, every gram counts. Enter Bellroy’s Lite Travel Pack, made with a lightweight but durable 100% recycled nylon. Available in 30L and 38L sizes weighing 950g and 1kg respectively, the backpack offers a host of travel-friendly features without weighing you down. Clamshell access and inbuilt organization in the main compartment make it easy to pack and retrieve gear on the go, while two exterior front pockets and loop attachment points provide easy access to frequently used items. Additionally, the pack has an externally accessible 16″ laptop compartment and three carry options including stowable backpack straps, a side handle for briefcase mode, and a luggage pass-through sleeve.

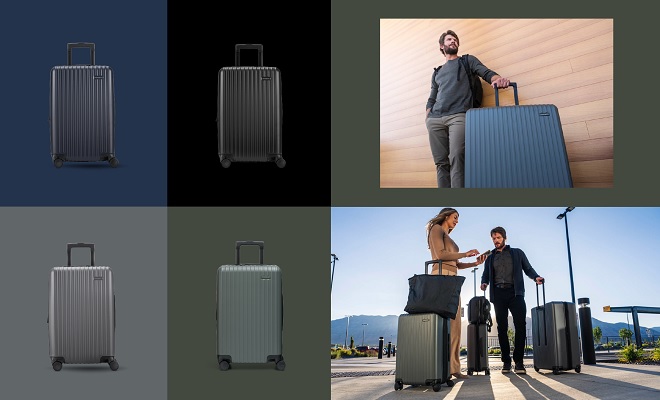

Nomatic Method Luggage Collection

Nomatic aims to deliver more efficient travel with their new Method Luggage Collection. Designed to be lighter, tougher, and able to accommodate up to 20% more than other luggage with the same dimensions, the collection offers both a Carry-On and Check-In option in four colorways. The expandable design allows you to adapt to changing loads, while interior pockets and a compression system keep gear tidy and secure on the move. The cases feature smooth 360-degree spinner wheels and a TSA lock.

Peak Design Coyote X-Pac Bags

Peak Design first introduced their Coyote X-Pac as part of a collaboration project last year. But the fabric proved so popular that it’s now part of Peak Design’s permanent lineup. Available across 11 new Travel and Everyday bags, the Coyote fabric is made from recycled fishing nets and is fittingly called X-Pac VX-21 Ocean Edition fabric. The exclusive Coyote colorway is available across a variety of styles including backpacks, duffels, slings, pouches, and camera straps.

Our Best New Gear guides are written by David Vo and Catherine Baecker-Khoury.

Carry Awards

Carry Awards Insights

Insights Liking

Liking Projects

Projects Interviews

Interviews